I love this time of year. I love the jack o’ lantern decorations, the pumpkin treats and the smell of chill in the air. Most of all, I love the excuse to curl up with a book of ghost stories and dark tales.

When you think of legendary Gothic characters, you probably think of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, maybe of Dorian Gray or Dr. Jekyll. I love these books, too. But my favorite spooky stories are those of the “female Gothic,” the dark subgenre that eschews dark forests and forbidden castles for the more disturbing horrors of the everyday. Women writers like Shirley Jackson, Daphne du Maurier and the Brontë sisters thrived in this space, writing about the terrors of patriarchy and societal expectations as well as of haunted houses and ghostly worlds.

But while many a high schooler knows Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre, far fewer have heard of

Ann Radcliffe, Mary Robinson or Mary Roberts Rinehart — women whose works’ popularity once eclipsed that of the now-classic canon. Over the next week, I’ll be profiling a handful of these fascinating writers for subscribers. But today, I am dying to talk about Mary Robinson, the person Samuel Taylor Coleridge called “a woman of undoubtable genius.”

Before she was lauded for her singing, acting and writing, Mary Robinson was just a 14-year-old girl teaching dance lessons in Little Chelsea, London. In the 1750s, her father abandoned his young family to live abroad with his mistress, but the enterprising Mrs. Robinson turned their manor house into a finishing school with students from all corners of English society.

Word of Mary’s sweet singing voice reached renowned thespian David Garrick. Garrick insisted on tutoring Mary in the world of theater, and once she left her job at the school, she dove into the world of dance, music and acting. But her marriage to Thomas Robinson, a clerk who boasted of his massive inheritance, cut her studies short.

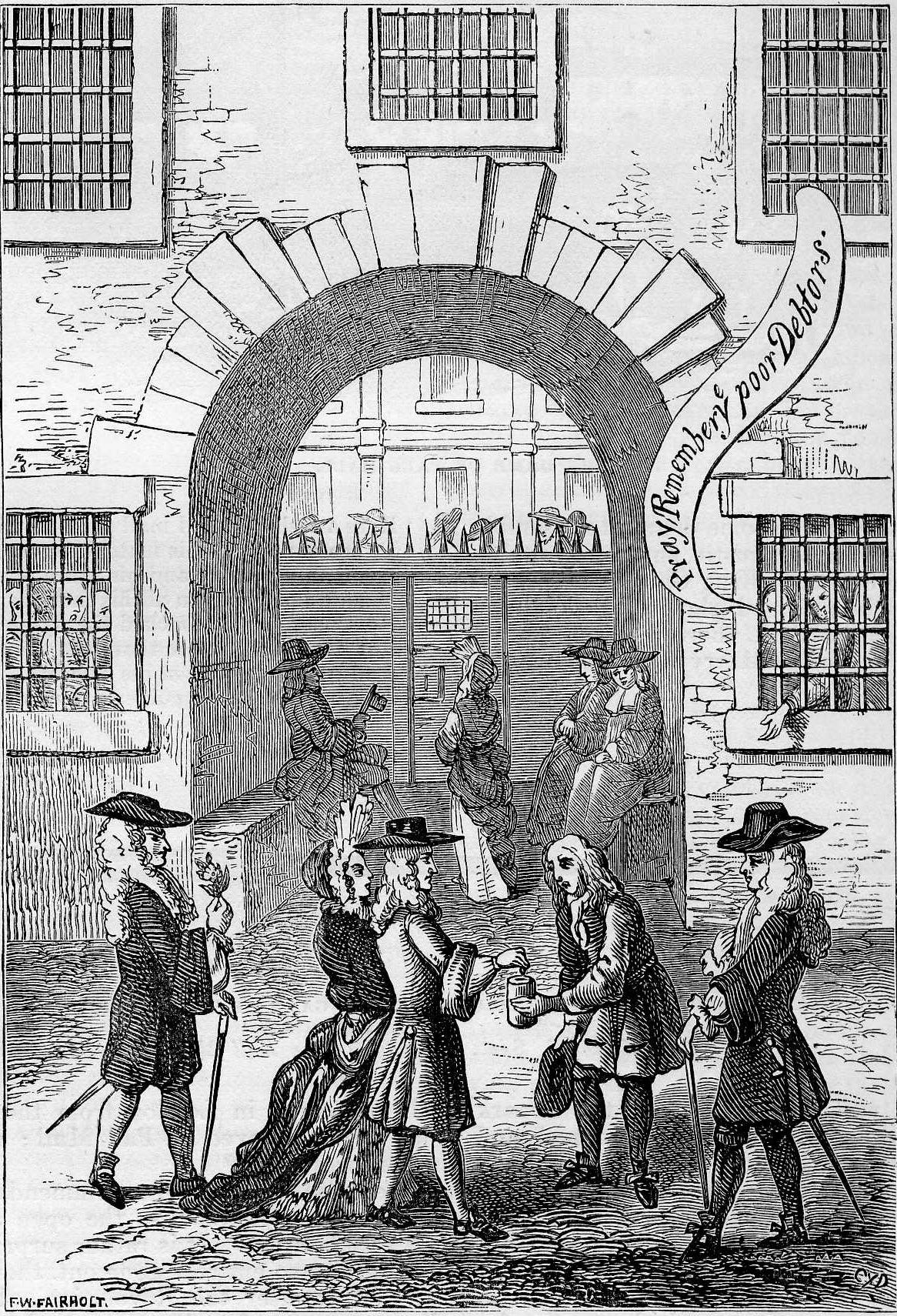

Before she’d even turned 20, however, Mary’s husband revealed the enormity of his subterfuge — no such long-promised inheritance existed, despite his flagrant consumption and champagne taste. The spending didn’t stop; by 1775, Thomas, Mary and their infant daughter had lost their house and moved into Fleet Prison, a squalid debtor’s prison.

After many months in such conditions, Mary took it upon herself to make some money and save her family. A benevolent duchess, Georgiana Cavendish of Devonshire, offered to publish two books of Mary’s poems, and their subsequent success freed Mary and her family. Readers were so touched by her moving depictions of life after a broken heart. Critics called her “the English Sappho” in celebration of her tender love verses (I have to admit I was bummed to see there wasn’t a queer connection here! At least not one we’ve uncovered yet?).

After leaving Fleet Prison, Mary returned to the stage in triumphant fashion, taking on the role of Rosalind in Shakespeare’s “As You Like It.” After a star turn as Shakespeare’s Perdita, Mary caught the eye of George IV, then the Prince of Wales. Rumors swirled that he’d offered her 20,000 pounds to leave the theater and her husband behind. She did — and within the year, he’d dropped her, to the delight of the tabloids.

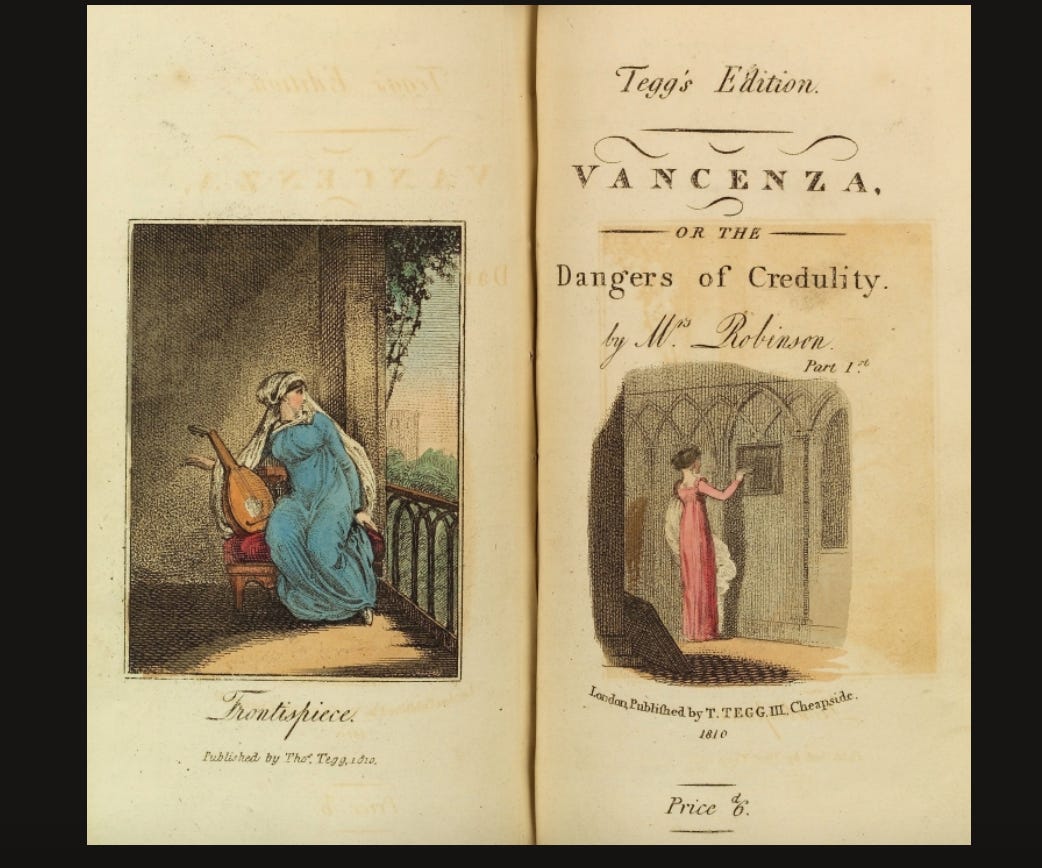

Needless to say, Mary knew the horrors women faced in the 18th century all too well. In 1792, she published her first Gothic novel, Vancenza; or The Dangers of Credulity, a story of an innocent young woman who falls in social stature after her conniving friends and devious suitor plot to destroy her. Contemporary reports say the book sold out its first printing within a day; the themes Mary explored, of women regularly exploited by and trapped within patriarchy, drummed up some serious literary controversy. Her subsequent novels — The Widow; or, A Picture of Modern Times and Angelina — failed to match her earlier success. But her profile, still high from her literary success and that much-ogled romance with the prince, gave her a political platform. She wrote multiple pamphlets on women’s rights and “the injustice of mental subordination.”

But at the same time Mary’s writing embraced the political and dark alongside the romantic and sweet, her health was failing. She died at age 44 in 1800. In her final days, she tried desperately to bequeath what little remained of her estate to her daughter. But ultimately, patriarchy won once more, turning over control to her estranged husband Thomas, who finally had the inheritance of which he once bragged.

Mary’s daughter Maria became a novelist herself. She published her mother’s memoirs posthumously.

More on 🦇:

The real life heroines of the early gothic, Reactor Magazine

Weird Women: Classic Supernatural Fiction by Groundbreaking Female Writers, Leslie S. Klinger and Lisa Morton

Was there ever a “female Gothic?” Nature Magazine

More from me:

My latest column for The Wall Street Journal explores the importance of estate planning for people of all ages — even us “young” folks!

Did you read Splinters or This American Ex-Wife or any of this year’s best-selling divorce memoirs? I wrote about the emergence of this subgenre for Glamour! And if you’re unfamiliar with some of these titles, I even curated a reading list, just for you.

Do you remember the Royal Diaries books from when you were a tween? Follow me on TikTok — I’m reviewing them as I reread them!

I want to hear from you! Get in touch with possible story assignments, share opportunities to collaborate or send your own recommendations for women to know. All you have to do is reply to this newsletter to get the convo started.