A Woman to Know profiles once-forgotten women from history. To support this work, become a paid subscriber. You’ll get access to the subscriber-exclusive Friday editions, but you’ll also be able to read the entire back catalogue — that’s nearly 10 years of women to know!

If you’re interested in recommending a woman to know, sponsoring a single edition (or a week of subscriber-only editions!), partnering on a project or otherwise just want to get in touch — reply to this newsletter.

In 1860, the Clotilda docked in Mobile Bay in Alabama. The Yoruban girl who later came to be known as Matilda McCrear was aboard, then just two years old; another kidnapped passenger, named Redoshi, had just turned 12. They were among 110 West Africans held captive aboard the ship.

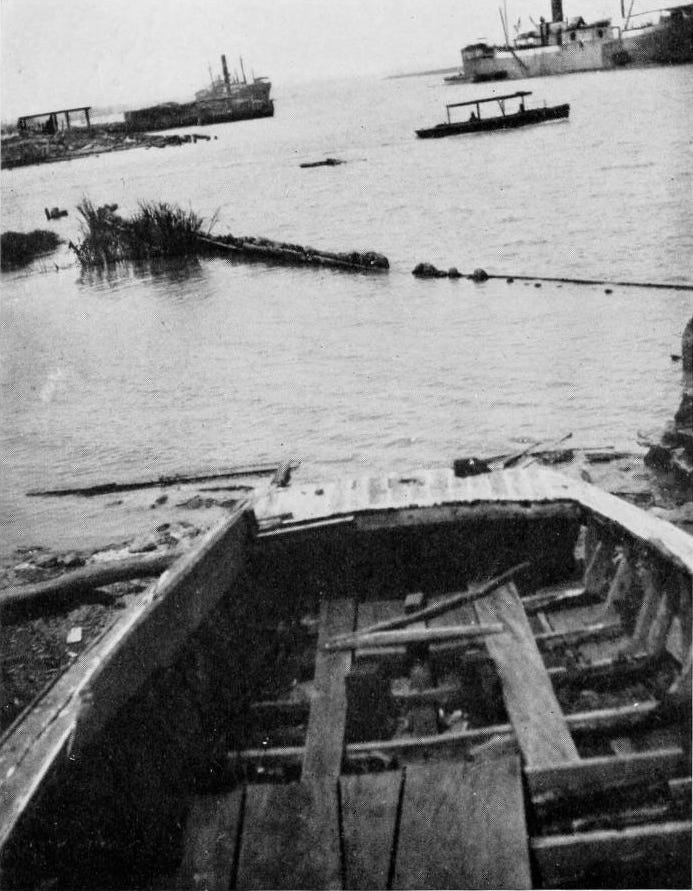

In 1808, the United States claimed to have abolished the Atlantic slave trade with the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves; but vessels like the Clotilda still smuggled enslaved Africans back and forth across the Atlantic. After the Clotilda brought Matilda and Redoshi to Alabama in 1860, the captain set fire to his own ship and hid the scorched evidence — that of the last slave ship to dock in America — along the shores of Mobile Bay.

In Alabama, Redoshi was forced to “marry” Yawith, another kidnapped African from the Clotilda. She was a child. Yawith had a wife and children back in Africa. The slavers didn’t care, and they didn’t care that Redoshi and Yawith didn’t speak the same language. She recalled the horror of the auction block:

I was 12 years old and he was a man from another tribe who had a family in Africa. I couldn’t understand his talk and he couldn’t understand me. They put us on a block together and sold us for man and wife.

The plantation owner who bought the “married couple” gave them new names: “Sally Smith” and “Uncle Billy.”

Matilda, whose Yoruban name has been lost to history, was still a toddler when she arrived in Alabama. An Alabaman named Memorable Creagh bought Matilda, her mother and two of her sisters, giving Matilda her first American name and his own surname, “Creagh.”

The first year on the plantation, Matilda’s plotted an escape for herself and her daughters. Matilda recalled hiding with her sisters in the swampland for hours, evading capture until the overseers’ dogs caught their scent. The story “brings to light the miserable treatment that they endured even as young children and shows how profound was their sense of dislocation and desperation to return home,” one historian said.

On January 1, 1865, the Emancipation Proclamation liberated all enslaved people living in the Confederate states. But as the Clotilda transported Redoshi, Matilda and their families more than 50 years after the legal abolition of the slave trade, so did the supposed emancipation fail to free Redoshi and Matilda. They remained enslaved until 1865, at the end of the Civil War.

The celebrated author Zora Neale Hurston interviewed Redoshi and another man from the Clotilda, Cudjoe Lewis. For many years historians believed Cudjoe, who died in 1935, to be the last survivor of the Atlantic slave trade.

In the 2010s, when historian Hannah Durkin uncovered the stories of Redoshi and Matilda, she said that so many of the other documents and archives previously regarded as primary were actually recorded from a slave owner’s point of view. She published her findings to “add hugely to our understanding of transatlantic slavery as a lived experience.”

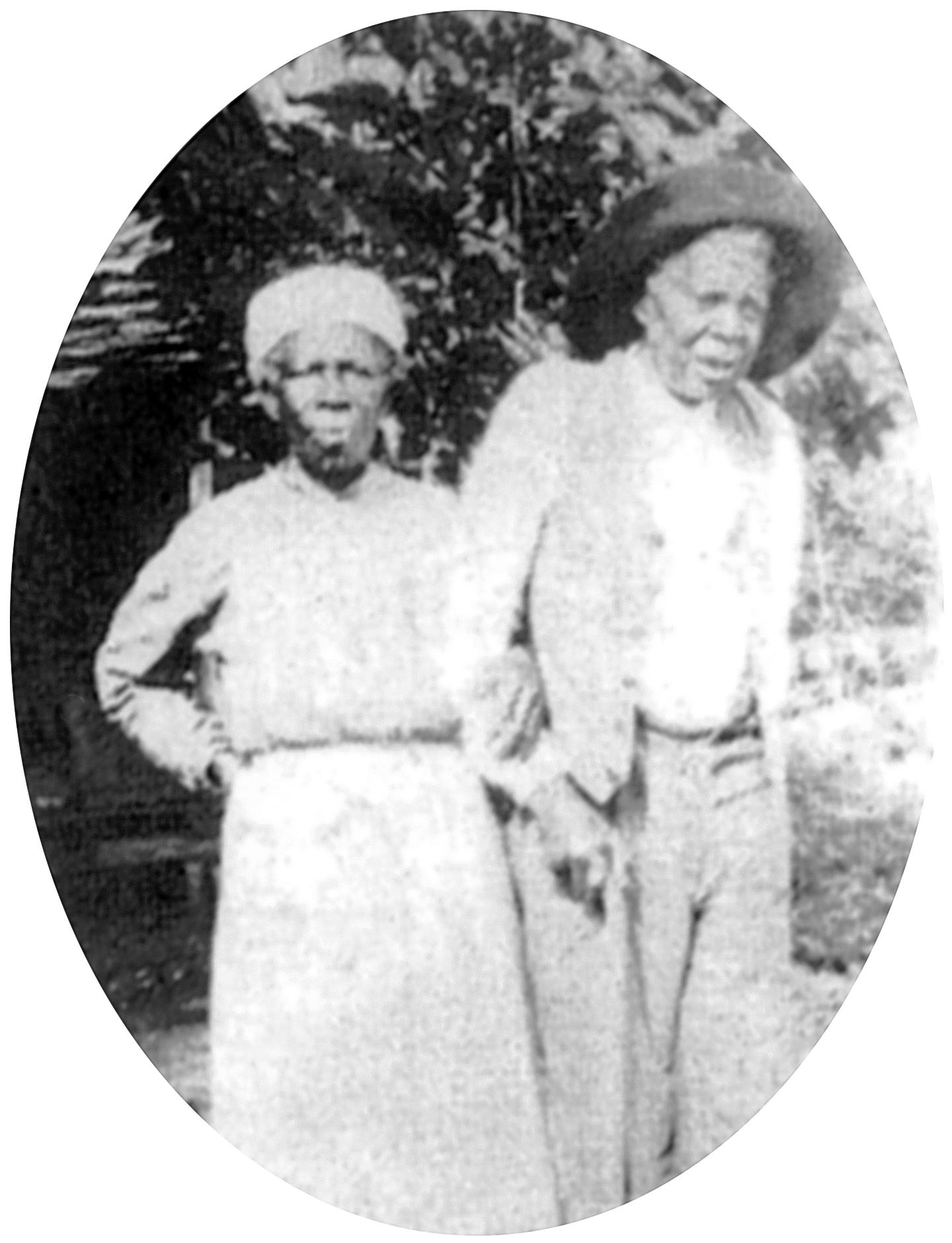

We know that its horrors endured in living memory until 1937, and [these documents] allow us to meaningfully consider slavery from a West African woman’s perspective for the first time. Rarely do we get to hear the story of an individual woman, let alone see what she looked like, how she dressed and where she lived.

Later in life, Matilda and Redoshi reunited. They had each continued to work as sharecroppers in Alabama, working the same land for the men who had enslaved them. Matilda changed her name, dropping the slaveowners’ “Creagh” and instead adopting “McCrear.” She wore her hair in a traditional Yoruba style and began a decades-long relationship with a white German man, having 14 children with him. Redoshi had one daughter with “Uncle Billy,” the man the slave traders had forced her to marry. She passed her native religious traditions on to her daughter, emphasizing the importance of the preservation of their West African culture.

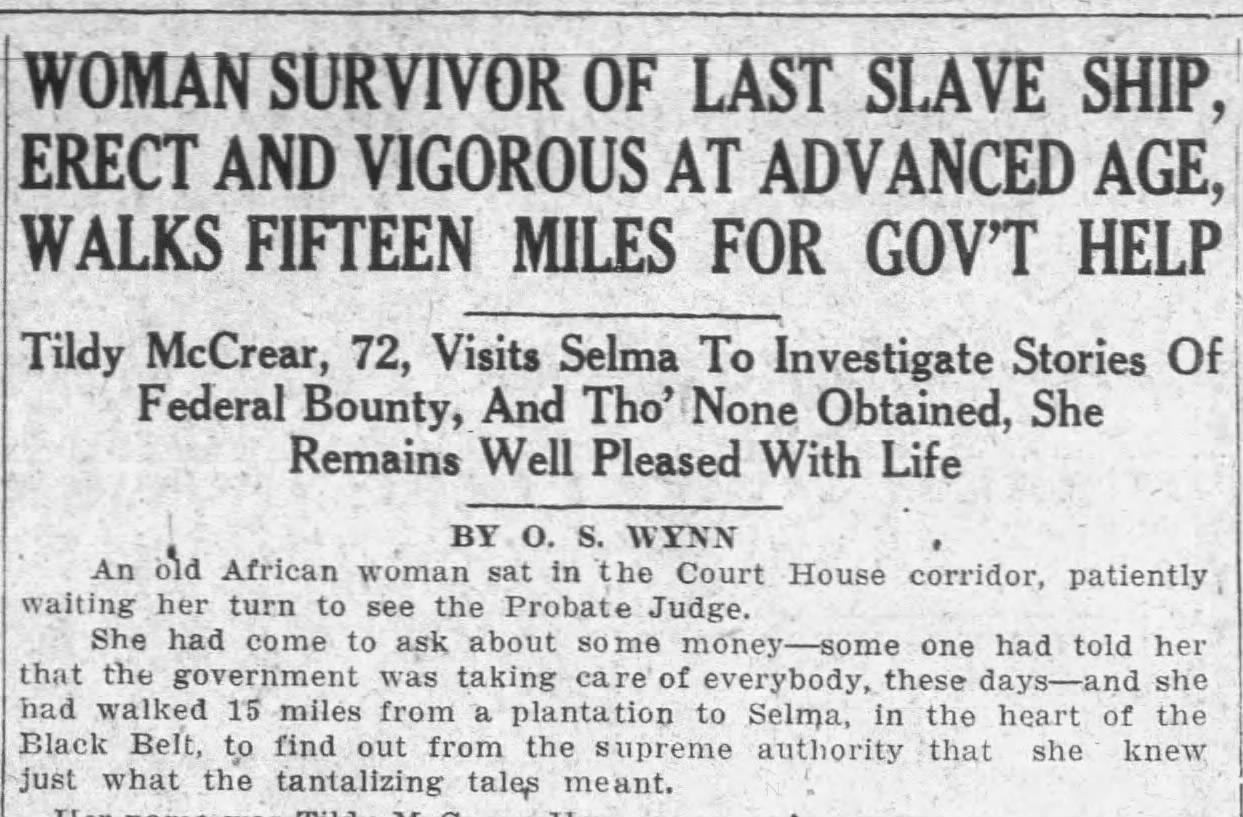

Matilda and Redoshi reconnected in 1972, when both women were well into their 70s. Matilda had heard tell of Cudjoe Lewis receiving reparations from the government once he provided evidence of his journey on the Clotilda. Matilda and Redoshi traveled more than 300 miles to meet with Cudjoe and have him confirm his recollections of them. From there, Matilda petitioned her case before a judge in Selma — only to be denied.

She and Redoshi lived the rest of their lives in Alabama. Redoshi died in 1937, Matilda in 1940.

In 2020, Dr. Durkin shared her findings with 83-year-old Johnny Crear, Matilda’s grandson. His grandmother had never shared her connection to the Clotilda with him:

Her story gives me mixed emotions because if she hadn’t been brought here, I wouldn’t be here. But it’s hard to read about what she experienced.

More on Matilda and Redoshi:

Uncovering The Hidden Lives of Last Clotilda Survivor Matilda McCrear and Her Family, Hannah Dorkin at Newcastle University

Slave Wrecks Project, the National Museum of African American History and Culture

Researcher Identifies the Last Known Survivor of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, Smithsonian Magazine

The Case for Clotilda, Archaeology Magazine

She Survived a Slave Ship, the Civil War and the Depression, The New York Times

The Life of America's Last Slave Ship Survivor, History Channel

More from me:

I’m reading: Piranesi left me speechless. This is a book people had been telling me to read for years — good reminder that if multiple people are telling you to pick something up, it’s often worth the time!

I’m writing: One of those weeks where I’ve had pitch after pitch after pitch rejected. I’m coming up on one year of freelance life — it’s not for the faint of heart! A question prickles my brain: am I faint of heart?

I’m doing: My former Girls Write Now mentee Shanai Williams is performing at Radio City Music Hall! Get your tickets for the Garden of Dreams Foundation’s springtime show on April 8.

I’m recommending: Wear your dang nightguard. I’ve had a jaw click and some nerve pain bothering me this last week — the dentist promised it’s nothing more serious than tax season stress and nightguard neglect. Whatever.

I’d love to recommend Erika Mann! I have only recently learned about her.