A Woman to Know profiles once-forgotten women from history. To support this work, become a paid subscriber. You’ll get access to the subscriber-exclusive Friday editions, but you’ll also be able to read the entire back catalogue — that’s nearly 10 years of women to know!

Wanna get in touch? Reply to this newsletter.

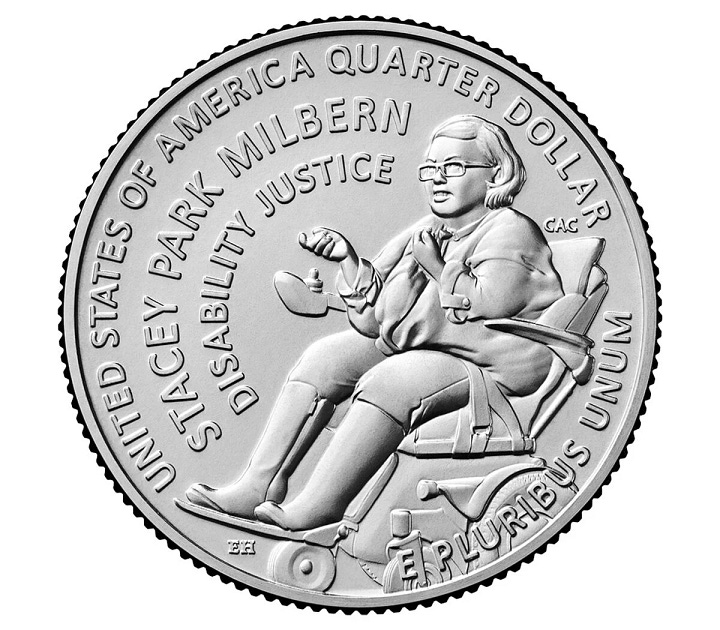

We wouldn’t know the word “disability justice” without the work of Stacey Park Milburn.

In 1987, Stacey was born with congenital muscular dystrophy, often abbreviated as CMD. She was born in Korea but grew up in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where her father, a U.S. Army officer, was stationed.

Stacey realized early on just how little awareness her peers had about the “totally different reality” disabled people inhabit. As a teenager, she fought to change that, joining multiple state commissions to promote disability rights. Her work added disability history to her high school curriculum and created new programs and forums for young people with disabilities. She wrote a personal blog chronicling her life with CMD and her hopes for the disability rights movement.

In 2005, when she was just 18 years old, Stacey worked with other activists to coin the term “disability justice,” revolutionizing a movement “dedicated to ensuring the perspectives of traditionally marginalized groups within the disabled community weren’t left out of the fight for disability rights.”

In 2011, Stacey moved to the Bay Area to join the community’s decades-long history of disability advocacy work. She founded the Disability Justice Culture Club and held club gatherings in her home.

There honestly isn’t space in this newsletter to list all of Stacey’s honors and accomplishments. As she said in a 2017 interview with the Disability Visibility Project:

I would want people with disabilities 20 years from now to not think that they’re broken. You know, not think that there is anything spiritually or physically or emotionally wrong with them. And not just people with disabilities, but queer people, gender nonconforming folks and people of color. And all of the people I think that society really pushes down and out.

At the height of the coronavirus pandemic, Stacey worked with the club to distribute masks, hand sanitizer and other necessities to the unhoused in the Bay Area. “Oftentimes, disabled people have the solutions that society needs,” she said. “We call it crip — or crippled — wisdom.”

Just a few months later, she passed away from surgery complications. She died on May 19, 2020 — her 33rd birthday.

More on 🌺:

Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong

Stacey Milbern, a Warrior for Disability Justice, Dies at 33, The New York Times

In Her Own Words: Remembering and Honoring Stacey Park Milbern, Google Arts & Culture

Loving Stacey Park Milbern: A Remembrance, Disability Visibility Project

What Disability Justice Activist Stacey Park Milbern Taught Us, KQED

Stacey Park Milbern, The National Women’s History Museum

More from me:

As you read this, I’m sitting on a beach in Montauk right celebrating one of my best friends in the world, Everdeen Mason — you should subscribe to her wonderful newsletter about sci-fi and fantasy books as a birthday present.

I’m writing for History.com now! My most recent story is all about Kubaba, the only woman to appear on the Sumerian King List.

Wrote about some exciting news in my life (and unlocking a new anxiety! Ha ha!) for The Wall Street Journal.

I just finished Shark Heart: A Love Story, and while the ornate writing style isn’t quite my usual thing, I found the story itself incredibly moving. I also picked up Perfect Little World to sate my Kevin Wilson cravings (I’m still on the library hold list for his new book!) but honestly couldn't get into it and dropped it after 100 pages. But I took a ton of books to the beach! More on that soon.